Excerpts from my journal during my first trip back to Damascus

The desert greets us from below the wings of the plane. Dry lands where even the olive trees and the jasmine flowers suffered under the regime. Fairuz waits for us in the car - smiling with a hint of melancholy. The first thing my cousin Moaaz says to me is طولتوا علينا - what took you so long? The first glimpses out the window of my cousin's car, a window capturing within it a landscape I never thought would be anything more than a distant memory.

Comments about my hair and appearance. From the moment I arrived I looked peculiar. Bil Ghourba, far abroad, I had changed. They're staring at you like you fell from the sky! my friend remarks - I look too strange to fit in. My clothes, my hair, my glasses, the cameras I carried, my accent, and even the way I stop and look around. I was clearly not from here. Is your friend a foreigner? asks the museum ticket vendor, judging whether to make me pay the tourist entry price.

My name is called out in the restaurant, I turn around and see a man collect his order. I was not the only one anymore. They asked for my full name at the mosque, we were trying to gain access to climb up the minaret - I didn't have to spell it, I didn't have to say it again. They knew my name, they knew me.

Even in our neighborhood, a small mountainous area in the newer part of on the damascene outskirts, we encounter returnees; full of emotions from finally ordering a tea in the place they called home for so long. In the cafe she told us her name, an old one no longer used these days, said she worked for the UN, turned out she was in the same office as my dad back in her time. She told us of the people she still had here, and those she had lost. There we stood, all three of us returned from the Ghourba, with shared stories and shared pain.

I find my old books, my old toys, old photos, and even my father's old clothes in the locked closets of our apartment. I am overwhelmed with memories flooding back my mind, memories long forgotten. I take out my dad's shirts and ask him if I can wear them. He smiles as I try the first on.

Three men in green go from shop to shop - AK in one hand, clipboard in another. No identifying symbols or clothes, and yet everyone seemed to know them. They walk through the shops and ask for permits, they point out irregularities, and they impose the law, much of it seems to dictate an effort at beautifying the area - these cables cannot hang here, these items cannot be displayed there.

From the moment we jump in the cab, to the slowing down of the wheels, two friends catch up while I sit in the back my gaze wandering out the window onto the buildings, the trees, the mountains, the people, who have held on to so much despite it all. My dad spoke to every taxi driver like they had always known each other, he always did and I always sat in the back as a kid and listened. Here I was a whole lifetime later, my eyes glued to the window again while my father's laugh echoed from the front passenger seat.

Sand and dust covers the car, politics fills it. In the Micro, a small shuttle bus used as the main mode of daily public transportation, people share bread, opinions, complaints, and memories. To pay for the fare, people pass money from the back seats, bills jumping from hand to hand, all the way to the driver. Each hand reaching out to bring the money just a little further.

Trees, grass, bushes, fruits, and even flowers, find a way to grow on the side of the street despite the harsh climate, the neglect, and the suffering. Just like the people of these lands. Exhausted looks on many of their faces, hardened by the years. Faces that still manage to smile and joke, resilience coming from a place of need.

My aunt grills me and tells me to promise to read the quran every day. Nothing else matters in this life and no one will help you but God. I wonder what my life would have been like, had I grown up in Syria, and not so far away.

Surrounded by Syrians my age at my cousins place. All his friends were invited over for a barbeque in the garden. On the one, we celebrate his graduation. I left him when we still played pretend shooting and building hideout bases in that same garden. On my first full day upon my return we celebrate his completion of university and remember all the years that were stolen from us. All this time we were unable to see each other. Hours and hours of joking and laughing with them. Everything else was too serious, everything brought back pain and unwanted memories. All they had to share were jokes to laugh everything away.

The next day I found myself sitting in between Moaaz and my Syrian friend, Alaa, living in Barcelona, overlooking Mashrou Dummar from above. I had gotten to know Alaa in Istanbul, spent time with him in Paris and Barcelona, and now here we were crossing paths again in Damascus. Quickly I realized the two of them had more in common than I did with my own cousin. They knew the same people, the same jokes, the same neighborhood drama, the same restaurants, even the same hangout places in damascus. My cousin was happy I spent my time with people like him, it meant something of him was still present in my life all these years. it meant despite the distance, I had found a piece of damascus back again in all these cities I frequented.

Abu Ayham picks us up in his shuttle car, and takes us for breakfast where Fairuz waits for us again. On the way there, he fills us in on the newest changes, the political and the cultural. The same men in green from the market show up for breakfast too, part of the community, and known by name. No one shows any signs of discomfort or fear. Gone are those days.

Bread is sold on the side of the street. Where people used to stand for hours in line at the bakeries, all to get a single wrap of bread, it is now sold in abundance on the side of the road. Men, women, and young children carry the bread and wait for passing cars to stop and pick up bread. My father would stop and get some even if we didn't need any.

At Tete's, my grandmother, place, I remember sitting on the floor surrounded by all my relatives talking, sleeping with my cousins, endless stories shared and passed around. In the same sitting room I remember sitting in February of 2011 as everyone surrounded the TV with Al Jazeera reporting on the latest from the beginning of the Arab Spring. Protests starting in Tunisia, moving over to Libya and Egypt, like a wave inevitably moving towards Syria. I had just come back from Vienna for a short trip to visit everyone. I sit here in the same room 14 years later and fall asleep on the couch.

I leave Tete's house and hop on the first micro going to the city center. I observe the people that get on, those that pass us through the window, and try to imagine my dad in his youth. From Mazzeh Jabel to under the Jusr Al Hurriye, renamed from President's Bridge to Freedom Bridge. I hop on another micro that takes me all the way to Dummar Church. What was it like for my dad as in his teenage years here. He left Syria in his early twenties and spent his life moving around every few years ever since. Dressed in his old garments, I walk in his footsteps, and try to see this city as he saw it.

"You Al Khaled's are all good hearted" I hear them say. Stories of my grandpa echo between my relatives as we drink tea at Tete's. I had few memories of him. He passed away when I was still very young, and yet I felt I knew how each story would go, how he would act and what he would say. I excuse myself and go to the bathroom, looking for a place to be alone for a moment as I feel the tears come back for the millionth time since I arrived.

The lingering scent of yasmin and perfume overwhelmed by the smell of petrol - and yet my clothes remain clean no matter what. Dry air fills my lungs, dry wind blows in my hair. Despite the high temperatures, the weather feels cool and I don't break a single sweat. Thirty degrees here were like 16 back in Ireland.

My dad says he thinks this place would suit me, I don't look for extravaganza, I'm okay with simplicity he says. he says I'm like him when he was younger, able to take on any challenge, but that he's now too old to return to discomfort. Syria will need time to rebuild, you should be apart of that effort, but my time has passed, he explains.

Quranic fruits grow on the side of the street. Blessed are these lands that have seen many come and go. The oldest continuously inhabited capital has seen its share of history play out at its doorsteps. Christianity, Islam, Judaism, even Roman polytheism, all passed through here. Cats play and fight under a grapefruit tree while مصطفى اسماعيل recites on the radio.

I walk around Old Damascus and I can almost remember walking these alleys a thousand years ago. I come across a church from the first century, and remember the stories I heard of the companions of the Prophet ﷺ, stories Mu'awiyah and of Khalid Ibn Al-Walid, of Saladin and the crusades, of Paul the apostle the story of his conversion, of the Romans and their temples. In an old Armenian church, a lady in an orange blouse with a glistening silver cross around her neck says to me you're not from here are you? With frustration and sadness I explain that I was a mughtarib (one of the many Syrians who had been away for so long only to be able to return now). She gives me a warm smile and tells me there are many of us, and adds that I am welcome home.

تفضل البلد بلدكم

I attend an event on transitional justice. How are we to move forward now after everything that has happened? On the stage my friend Celine that I met in Istanbul. In the audience Alaa and Saeed sit by my side. A loud and vocal audience asks questions that don't have answers, they share stories and tears. When the regime fell we stormed Sednaya to get my father out, one explains. Trauma fills this country. We all want frontier justice for what happened, we all want it now. The volcano inside of us is inside every family, another audience member continues, no family was left untouched. Not a single person didn't lose people close to them. Audience members weep all around me. The stage concludes with a statement from an audience member... The government we have now are the children of the revolution. They're our cousins, brothers, and sisters. Those who were raised during the worst time of this country's history, and who fought to get it all back.

My cousin Moaaz drives us through the Jobar neighborhood. Destruction everywhere you look. Children, families, dreams, entire lives; schools, shops, homes; nothing remaining but rubble and dust. Amidst it all, golden sun rays glimmer through the holes in the buildings and reveal a poem with a photo of Bashar Al Assad, beneath shattered bricks and ashen dust. Not a single person, from our children to our elders, that doesn't curse him every single day, a taxi driver tells me. I tried to speak to as many people as I could. Understand through them everything that happened while I was kept away.

In Moaaz's car, he tells me the stories. Those of kidnappings, of the prisons and of torture, of gunshots and of wounds. I felt like puking, then crying, then I asked him to stop. Silence in the car broken by him saying this country took everything from us. We didn't get to catch up on the years we missed out on, he continues. I still see the same child in you, and yet you came back all grown up.

On my last morning in Damascus, Sham.fm plays on the radio in our living room. صباح الخير قدسيا (Good morning Qudsaya), the soft voice says as the early dawn sun drowns the apartment in its orange light. I leave my clothes in the closet as I get ready to leave. I leave them for when I return. This time, it won't take me 15 years to find my way back.

The below are photos captured on a Ricoh AF-2, a 35mm film camera I borrowed from a good friend of mine in Istanbul in preparation for this trip.

Syria from above

Traditional damascene house

Saeed, Alaa, myself, and my cousin Moaaz in order from left to right

The view from my bedroom window, overlooking Qudsaya

Hejaz Railway Station, built under the Ottoman Empire in 1907

Apartment building we used to live in during our 2009 sejour

Mashrou Dummar, also referred to as New Cham

My father (left), and family friend and storyteller Abu Ayham (right)

Masjid Al-Niman Bin Basheer in Mashrou Dummar

Al-Hamidiye Souq, holes in the metal roof are bullet holes left by French warplanes during the Great Syrian Revolt of 1925, when Syrians rose up against French colonial rule

A lecture within Umayyad Mosque, many would avoid lectures until now, as they would fear persecution and kidnapping by the regime

Bakdash, the oldest ice cream parlor in Syria (1895), making traditional Syrian ice cream (Buza)

Myself in the Umayyad Mosque square

The minaret we climbed with the mosque's management's permission

Umayyad Mosque, blending Roman, Byzantine, and early Islamic architecture

Umayyad Mosque, interior

Umayyad Mosque

Ruins of Roman temple of Jupiter (1st century AD), now entrance to Al-Hamidiye Souq

Breakfast with friends

Construction works on renovating the roads in Old Damascus

Moaz, Alaa, Saeed in order from right to left

Fallen minaret in Jobar, Damascus

Jobar, Damascus

Saeed and Moaz, a friend and my cousin respectively, amidst rubble in Jobar, a neighborhood in Damascus that was bombed pretty heavily

Going on a walk in our neighborhood, Qudsaya

The view of Old Damascus from the top of a minaret in the Umayyad Mosque

The view from one of our windows

Our kitchen in Qudsaya

Sunrise in our kitchen

Tea and snacks in my aunts garden.

Mashrou' Dumar, Syria runs largely on privatized solar energy - each family will set up panels on their roof to supply them with electricity

Tamr Hindi, a chilled drink made of tamarind, sugar, and water.

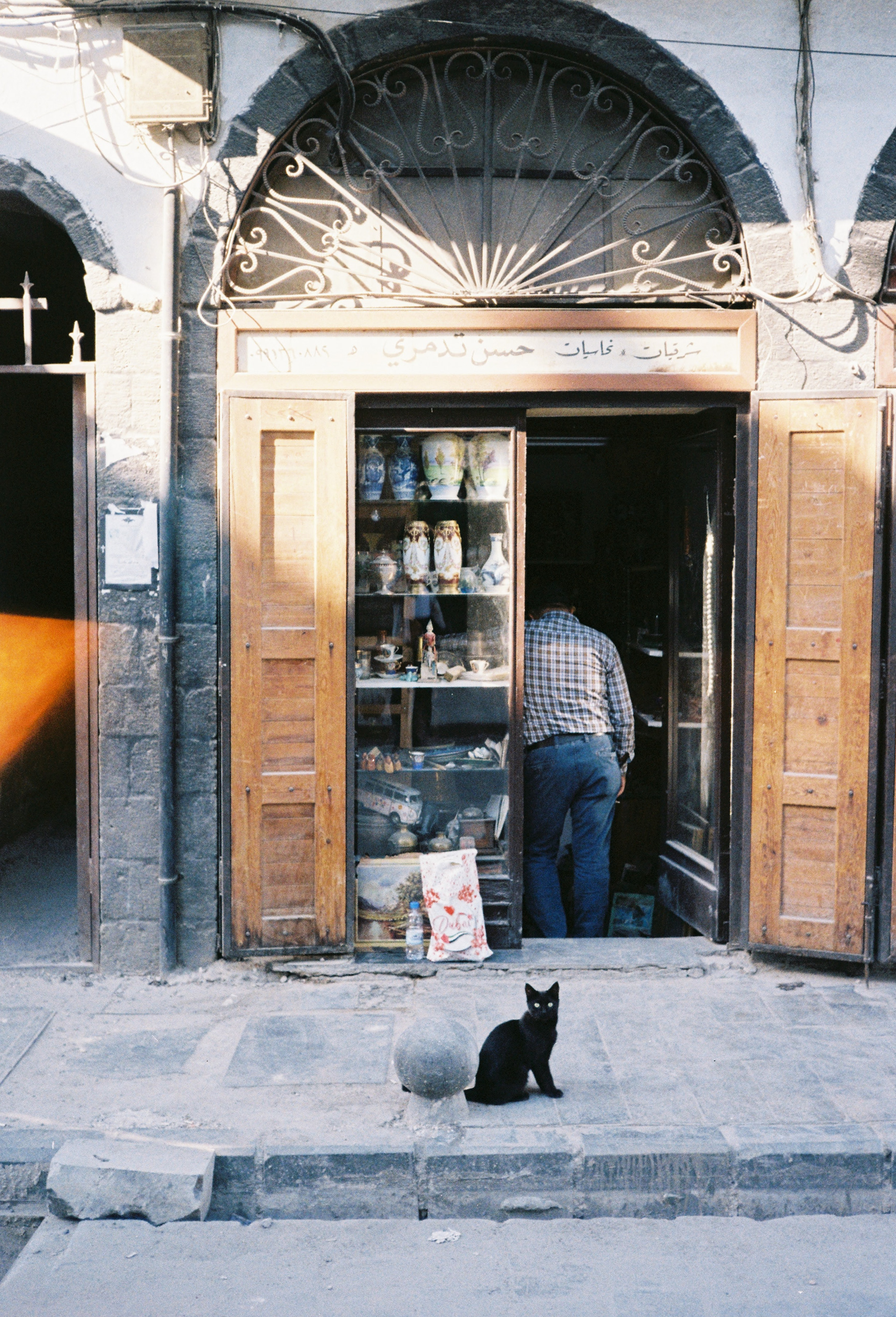

One of the entrances to Al-Hamidiye Souq

Alaa and Celine, two friends I met in Istanbul who crossed my path again in Damascus